Kidney stones may be tiny, but they pack a mighty punch. They are most known for being painful, hard-to-pass urinary deposits. These stones were thought to be largely insoluble. Now, research is shedding some light on the intricacies of kidney stones—and the results are stunning.

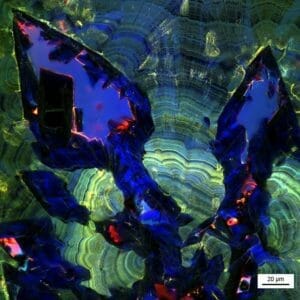

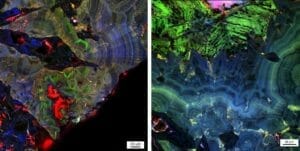

Much like the Great Barrier Reef, kidney stones resemble coral reefs or limestone formations. The deposits are made up of complex, calcium-rich rocks with layers that build up and dissolve over time. Unearthing these complexities is helping researchers determine better ways to provide diagnosis and treatment. The images are spectacularly beautiful, too.

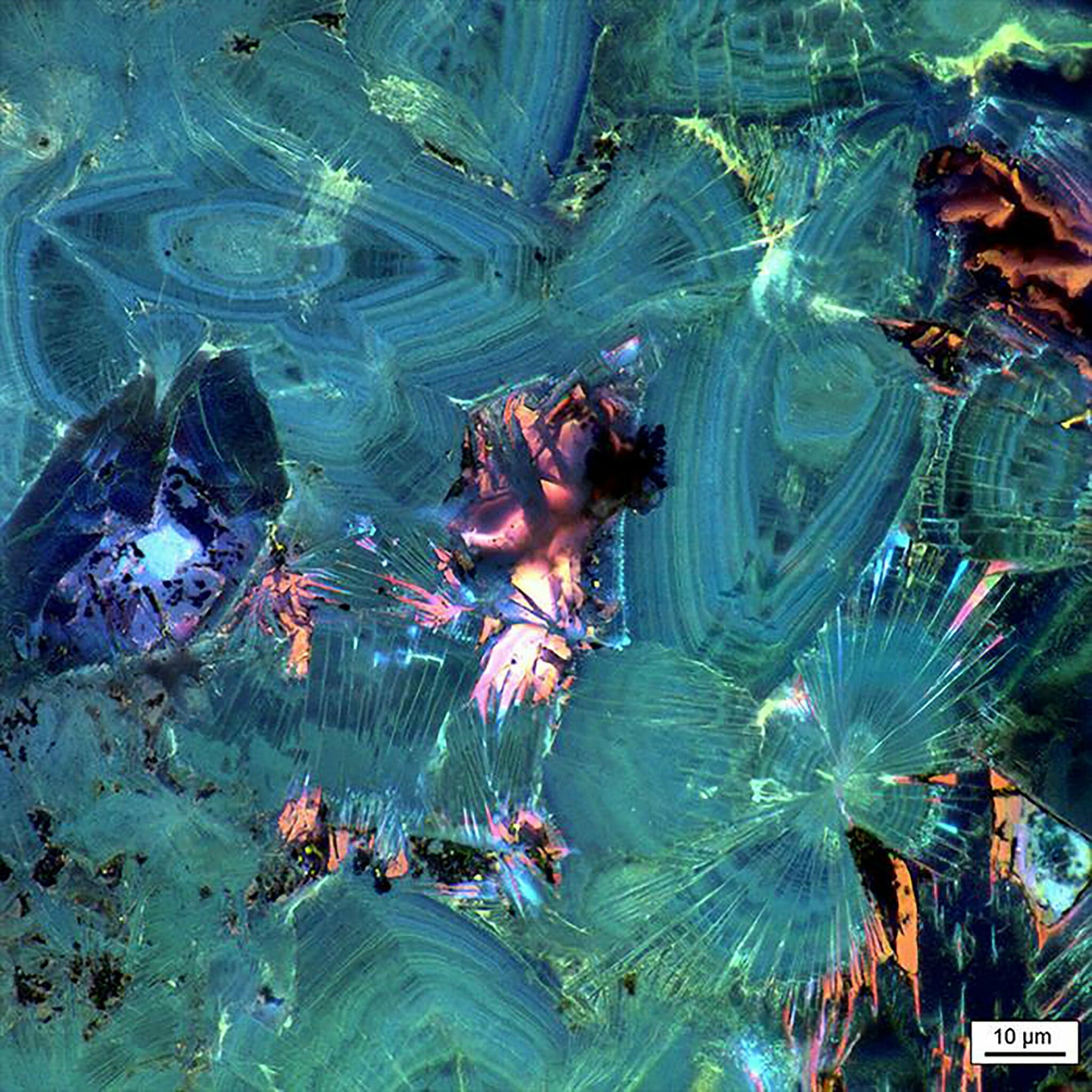

The study, published in Scientific Reports, analyzed thin slices of kidney stones in combination with optical techniques such as bright field, polarization, confocal and super-resolution nanometer-scale auto-fluorescence microscopy. Over 50 calcium oxalate (CaOx) kidney stone fragments were collected from six patients for analysis.

Geobiological approaches allowed the team to examine the chronological and spatial framework of crystal growth and layering patterns. Airyscan super-resolution microscopy is one of the high-resolution methods used to capture these colorful snapshots.

Here are the photo results.

The key finding of this study is that the kidney stones repeatedly dissolve in vivo.

“When doctors find that ugly, boring lump and discard it, they are throwing away the most precise record book we have — a minute-by-minute, layered history of the kidney’s physiology,” said Bruce Fouke, a geology and microbiology professor at the University of Illinois, who led the project.

More than 10 percent of the global human population is currently affected by kidney stones. For decades, doctors have relied on the molecular components and chemistry of a patient’s urine to form a care plan. It is now known that a host of other factors influence the formation of kidney stones. Further research on the changing composition of kidney stones could allow doctors to dissolve the stones in vivo—which means that patients would not have to endure the pain of passing stones or invasive procedures.