What is a Port?

IN THIS ARTICLE

A Port-a-Cath is an intravenous catheter that is placed under the skin in a patient who requires frequent administration of chemotherapy, blood transfusions, antibiotics, intravenous feeding, or blood draws. It is a central IV line, meaning that the catheter is threaded into one of the large central veins in the chest, which empties into the heart.

The vein which is used most often is the right internal jugular vein. This vein is preferred because it is very close to the skin and easy to find with ultrasound. It runs straight down to the heart and has the lowest risk for problems during placement of the catheter, and subsequent use by oncology nurses. Commonly called a port, the term Port-A-Cath is a combination of the words ‘portal’ and ‘catheter’.

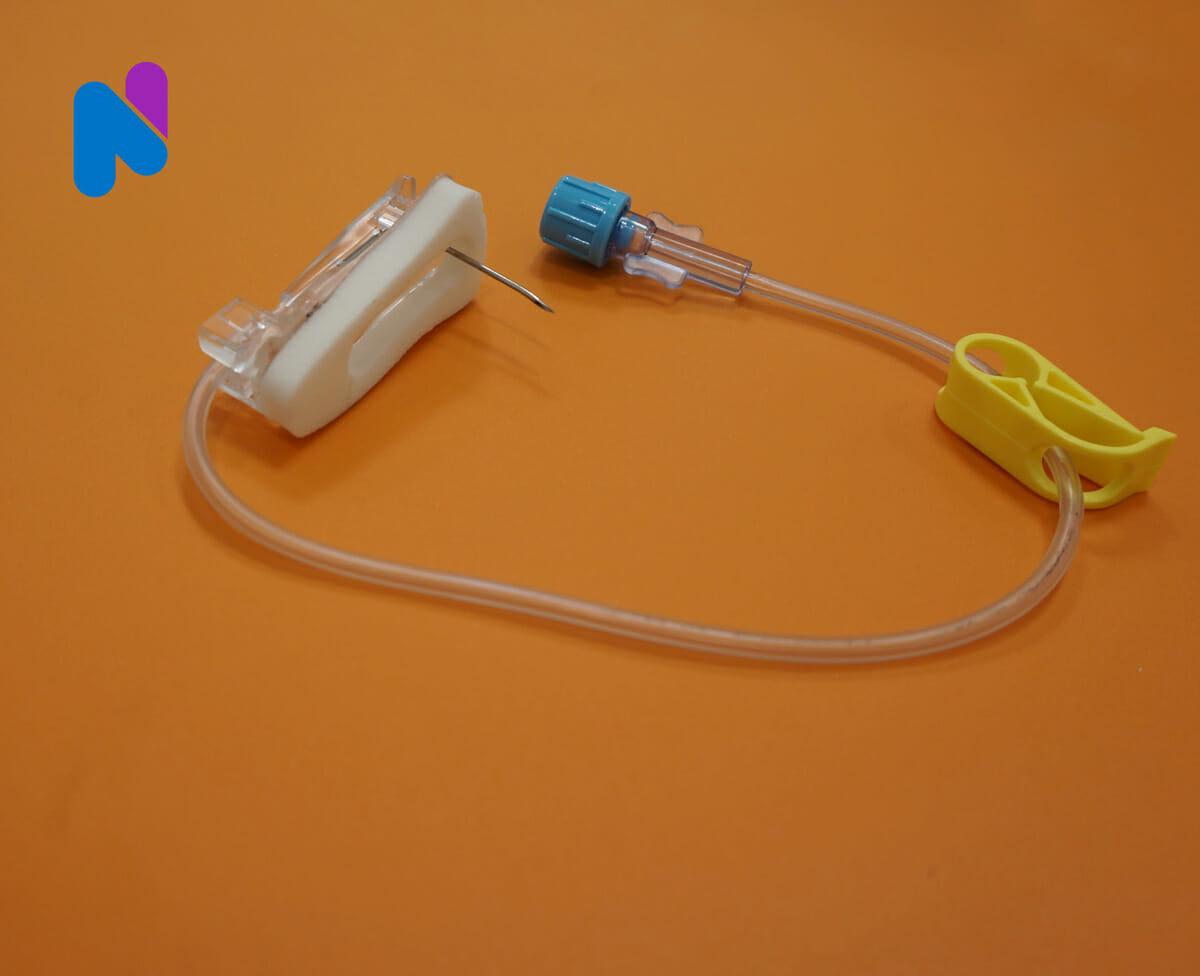

The ‘port’, or portal, is a small reservoir, about as big as a thimble, with a silicone septum that can be pierced with a needle. The silicone is self-sealing and can be punctured hundreds of times before the port must be replaced so it can remain in place for many years.

The ‘cath’ or catheter portion is the plastic IV tubing that attaches to the port. The catheters are placed by an interventional radiologist or surgeon, under local anesthetic, using ultrasound to guide the catheter into the vein.

The entire Port-A-Cath is inside the body, so that bathing and swimming are not affected. The port feels like a little bump under the skin, about the size of a quarter.1

Types of Ports

Common types of Ports are the single and double lumen ports, the P.A.S. port, the Groshong port, the side-access port, and the dome (or Omega) port.

The port used is primarily dependent upon the surgeon’s choice or availability within a medical facility. Dual ports are preferred from a maintenance standpoint because patients often require infusion of non-compatible medications and fluids which necessitate another I.V. access.

Additional I.V. access increases the probability of complications such as phlebitis, hematomas, and infiltration. The RN should be the patient’s advocate by helping the patient make the safest and most appropriate choice for venous access devices.2

- Dual Ports have separate reservoirs and separate catheters to each reservoir; however, the catheters are generally encased in one sleeve. The catheter end may have staggered tips terminating in the SVC/atrial junction or in the IVC if the Port. was placed in the abdominal wall. Each port requires individual care.

- The Groshong port is manufactured as a single or dual port. The tip of the Groshong PORTcatheter has valves typical of the tunneled Groshong catheter. No heparin is required with the Groshong catheter because of these valves. They are in a closed position when no I.V. fluids are infusing or no blood is being drawn. The side access port is accessible from both sides of the port body. A flat butterfly Huber needle is used to access these ports.

- The Omega, or dome port is shaped like a dome with a steel mesh encasing the dome.

Benefits of Ports

A Port, once, implanted, can stay in place for weeks or months. A physician, nurse, or medical professional can use it to.3

- Reduce the number of times a nurse or other team member sticks you with a needle. Health care team members call this a needle stick. This helps if you have small or damaged veins. These veins are often harder to take samples from. A catheter can also help if you need blood tests often or are anxious about needles

- Give blood transfusions or more than 1 treatment at once

- Reduce the risk of tissue and muscle damage. This can happen if medication leaks outside a vein

- Leaking is more likely with an IV catheter

- Avoid bruising or bleeding if you have bleeding problems, such as low platelet counts

- Lets you have some chemotherapy at home instead of the hospital or clinic. Continuous infusion therapy is given this way

Ports can remain in place for weeks, months, or years. Your team can use a port to:

- Reduce the number of needle sticks.

- Give treatments that last longer than 1 day. The needle can stay in the port for several days

- Give more than 1 treatment or medication at a time. If this is done, the port has 2 openings

- Do blood tests and chemotherapy the same day with 1 needle stick

Potential Problems with Ports

Use of an implanted port carries risks associated with a minor surgical procedure and vascular access. Potential complications include: internal bleeding, nerve damage, collapsed lung, fluid build up around the lungs, blood clot formation, and accidental cutting or puncturing of blood vessels.4

All wounds, including those purposely developed for the implantation of a port, contain some bacteria, all are “contaminated” to some extent. It should be noted that a wound can usually tolerate contamination of up to 100,000 organisms per gram of tissue, with the exception of streptococci, and still be closed successfully without infection.

Although exact quantitation of infection is impossible by visual inspection, in practical terms, when pain, redness, purulence, and induration are absent, port excision and wound closure, conjunction with antibiotic administration, appear to be safe and well tolerated in patients with device-related septicemia. This is true in our experience even when the device is the source of infection.

This practice simplifies follow-up wound care and provides acceptable cosmetic results.5

The most immediate risk from ports is excessive bleeding when they are implanted surgically. But the more common complications are blood infection and clotting.

Since a port is foreign material implanted in the body and accessed frequently from the outside, it can easily get infected. When this happens, bacteria grow rapidly in the bloodstream, causing dangerous contamination and fever.

At highest risk for infection are children younger than two years old and those whose ports are accessed more often.

Poor oral health can also trigger infections by sending bacteria from infected gums or decaying teeth into the bloodstream. Failure to adequately sterilize the port site before and after infusion can also cause infection.

A hematoma, or bruise, can occur on the surface (or septum) of the port device. It is caused by leakage of blood from the port to underneath the skin when the needle is removed from the port. If this occurs, the port should not be used, since the accumulated blood is an excellent growth media for bacteria, and may lead to an infection.

A hematoma is more likely with frequent, such as daily, access, or in individuals with inhibitors. However, this can easily be prevented by applying direct pressure over the puncture site once the needle is removed.

Clotting is another common problem with access devices. Up to half of patients with ports develop blood clots in the vein accessed by the port’s main line. Some patients develop clots in the device itself. Flushing the port with a blood-thinning medication can help prevent clots and possible infection. Physicians may also need to use blood thinners to treat clots. In some cases, the only way to break up the clot is to remove the port.

Other problems can develop when a port’s line, or catheter, separates from its reservoir. As a result, factor can leak into tissue surrounding the port. The port’s line can also get twisted, in which case the entire device must be reinstalled. As children grow, ports can also get displaced and cut off circulation in affected tissue. 6

When to Call for Help

While the likelihood of the above-stated problems occurring is relatively small, the following should be considered if there is a potential issue with the Port:7

When should I contact my healthcare provider?

- You have a fever

- You run out of supplies to care for your skin or port

- Your port site is red, swollen, or draining pus

- Your port site turns cold, changes color, or you cannot feel it

- The veins in your neck or chest bulge

- You have trouble using your port

- You have questions or concerns about your condition or care

When should I seek immediate care or call 911?

- Blood soaks through your bandage.

- You hear a bubbling noise when your port is flushed

- The skin over or around your port breaks open

- Your heart is jumping or fluttering

- You have a headache, blurred vision, and feel confused

- You have pain in your arm, neck, shoulder, or chest

- You have trouble breathing that is getting worse over time

Nurse Utilization in the Patient Care of the Port

When a nurse with working a patient with a Port, several considerations must be addressed, both in terms a preventive care as well as ongoing maintenance:8

- Perform proper flushing technique.

- Flush by creating a turbulent flow/scrubbing action thereby clearing out residue.

- Clamp tubing toward the end of the flushing action.

- Withdrawal of blood

- Draw blood sample

- Continue I.V. fluids as ordered or, if heplocked, flush with 5 cc heparin (100 units/cc).

- Send blood sample per policy and procedure of facility.

- Troubleshoot problems such as:

- Causes of occlusions

- Edema around Port

- Other situations encountered.

- Assessment of skin integrity at the Port Site

- When port is accessed, change dressing every 3 days .

- Change Port need every 6 days when port is accessed

- Perform terminal flush once per month, when the port is not accessed.

- Clear Port with heparin or Streptokinase or TPA

- Instruct patients regarding all aspects of Port and its care

- Have patient report swelling, redness, and soreness at site.

- Make patient familiar with design and function of port.

The insertion of Port is a highly invasive procedure, so a decision to insert such a device should take into account the patient’s condition, symptoms and illness. The device plays an important part in the patient’s recovery as it can aid diagnosis and treatment.

At the same time, the use of such devices can put the patient at risk of the complications discussed. The nurse has a vital role to play in helping to safeguard the patient against the potential risks associated with Ports.9

References

1 “What is a Port-A-Cath?” Mission Hope Cancer Center, 2016.

2,8 “The Use and Maintenance of Implanted Port Vascular Access Devices,” Nursing Link, 2016.

3 “Catheters and Ports in Cancer Treatment,” Cancer.net, August 2015.

4 . Bard Access Systems: PowerPort* Implanted Ports: Patient Guide, 2009.

5 Funaki, B., “Subcutaneous Chest Port Infection,” Seminars in Interventional Radiology, September 2005, Volume 22, Issue 3, pp. 245-247.

6 Law, B., “The Pros and Cons of Infusion Devices,” Hemaware, March 2009.

7 “How To Care For Your Implanted Venous Access Port,” Truven Health Analytics, 2016.

9 “Central Venous Lines,” Nursing Times, March 11, 2003.